by Melissa Petrini, Managing Editor for The Highline Journal

[This is a follow-up story to this story published last week]

Full Disclosure: I am a recently resigned Highline School Board Director, and have studied this over the past several years to understand for myself what was within the Board's oversight or control when it came to materials and books used. Sadly, I watched as this authority was stripped away slowly from local control, (read "parents and community") and given to those who are outside the control of the board.

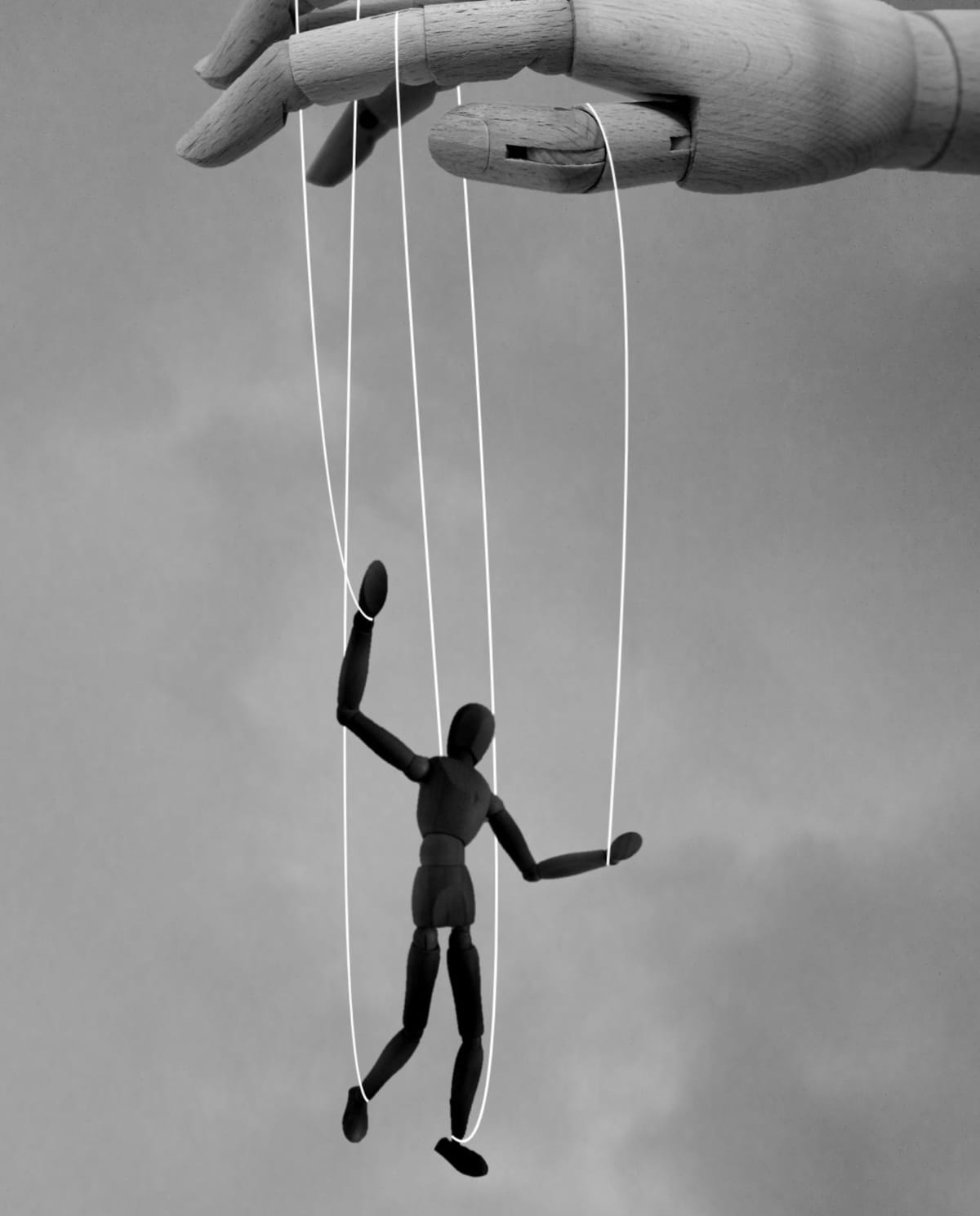

When parents in Washington State have concerns about what their children are being taught — whether in classroom curriculum or school libraries — they often turn to their elected school board for help and complain at a School Board public meeting. But increasingly, those elected officials have little to no real power over instructional materials. This was not necessarily the case in the past.

Instead, recent state laws and district-level policies have placed decision-making authority in the hands of superintendents and their appointed Instructional Materials Committees (IMCs). Meanwhile, school libraries are governed not by districts at all — but seemingly by the county library systems, which are exempt from most content regulations. A search through RCWs paints a story that has slowly eroded the local control away from elected officials and into the hands of unelected control.

So who really controls the books? Unfortunately, not your local school board.

From Local Control to Centralized Committees

State law once entrusted school boards with strong oversight of curriculum. But over time, laws and local policies have diluted that power. For example, updated Highline School Board Policy 2020, like many across the state, states:

“The Superintendent or designee shall establish procedures for the regular review of standards and selection of instructional materials... The Instructional Materials Committee (IMC) is the body that makes recommendations regarding potential adoptions of core instructional materials to the School Board based on the Superintendent-established procedure(s).”

In plain terms: the superintendent runs the process, appoints the committee (with board approval), and the committee — not the board — decides what materials go in classrooms.

The Complaint Process: Shielded from Public View

If a parent disagrees with a book or curriculum used in the classroom, they are directed to file a formal complaint with the IMC, not the board. But, unlike school board meetings — which are public, recorded, and transparent — IMC decisions happen behind closed doors, and the complaints themselves are not made public.

That’s what parent, Lauren Schmidt, discovered when she raised concerns about instructional content. Her complaint was rerouted to the newly appointed IMC, but she found no clear record of how it would be handled, no open meeting to attend, and no transparency to the public about her complaints — a stark contrast to traditional school board accountability. (You can also read her Letter to the Editor here.)

New State Law Further Limits School Board Authority

This centralization of authority was solidified in 2024 when the Washington State Legislature passed House Bill 2331, updating RCW 28A.320.230 and adding new sections to state education law.

Key changes under HB 2331:

- Appeals now stop at the superintendent: HB 2331 explicitly sets up a formal complaint and appeal process for decisions made by the IMC. Under the new law, if a parent, teacher, or principal disagrees with a material decision, they can appeal — but only to the superintendent or their designee, whose decision is final and not subject to further appeal.

- Decisions locked for three years: Once a decision has been made, the law states it “may not be reconsidered for a minimum of three years unless there is a substantive change of circumstances as determined by the superintendent.” This greatly reduces the possibility of parents or school boards revisiting a disputed curriculum choice.

- Board veto power restricted: HB 2331 also prohibits school boards from rejecting or prohibiting textbooks or materials on the basis that they include or relate to protected classes or identities (e.g., race, sexual orientation, gender identity), with limited exceptions. This directly weakens any potential for a school board to push back on content in response to parent complaints.

In effect, HB 2331 completes the transfer of authority over curriculum away from the school board and into the hands of the superintendent and unelected district staff, with minimal public oversight and no voter accountability.

Library Books: Out of District Control Entirely?

Even more surprising is the status of school libraries. While most assume that district officials or school boards oversee library materials, several Washington State laws suggest otherwise.

- RCW 27.12.321 abolished school district public libraries in 1966, transferring their assets to rural county library districts.

- RCW 9.68.015 and RCW 9.68A.120 explicitly exempt public libraries — including those operated by counties, municipalities, or universities — from state obscenity laws or restrictions on "erotic material" accessible by minors.

This means that even if parents object to library material in a school, the district — and by extension, the school board — may not legally control what stays or goes.

What the Law Does Still Say

There are still Washington statutes that suggest a role for school boards. For example:

- RCW 28A.150.230(2g) gives boards the authority to “evaluate teaching materials…in public hearing upon complaint by parents…”

- RCW 28A.320.230 still requires districts to have an IMC and board-adopted policy on instructional materials — though it now gives districts leeway in how many parents participate and vests final decision-making power with the superintendent.

But in practice, these powers are constrained — either by conflicting statutes, procedural hurdles, or administrative interpretation.

A Climate of Misinformation and Misdirection

Ironically, while some school board candidates or board members are labeled as “book banners” or extremists for raising concerns about materials, state and district policy gives them almost no power to remove books or change curriculum, even if they wanted to.

That leads to a broader public misunderstanding: parents think the school board has power it no longer holds, and that their concerns will be heard and acted upon. The reality is more complex — and far less democratic.

A Call for Transparency and Reform

This drift away from elected accountability raises serious questions:

- Why are complaints about curriculum handled in private by IMCs rather than in public board meetings?

- Why are school libraries exempt from the same rules that govern classroom materials?

- Why aren’t parents informed that the school board cannot actually resolve most content-related concerns?

The public deserves to know who is making these decisions, how those individuals are chosen, and whether they are accountable to voters or even visible to the public at all.

If educational materials are truly about serving students and aligning with community values, then those decisions should be made transparently — and with elected oversight.

Until then, the question remains: If the board doesn’t control the books, who does — and are they listening?

Key RCWs and Laws Referenced

- HB 2331 (2024) — Updated RCW 28A.320.230; appeal process and board restrictions

- RCW 28A.320.230 — Instructional Materials Committees

- RCW 28A.150.230(2g) — Board public hearings on complaints

- RCW 27.12.321 — School district libraries abolished

- RCW 9.68.015 / 9.68A.120— Library exemptions from material restrictions

Highline Journal Comment Guidelines

We believe thoughtful conversation helps communities flourish. We welcome respectful, on-topic comments that engage ideas, not individuals. Personal attacks, harassment, hateful comments, directed profanity, false claims, spam, or sharing private information aren't allowed. Comments aren't edited and may be removed if they violate these guidelines.